At the recent EcoBuilding conference here in Seattle, Bill Reid gave an energizing keynote on regenerative design. As sustainability has gained influence in design culture, the green building industry has developed a dizzying array of certifications, checklists, and performance standards that attempt to quantify sustainability for the market at large. Reid reminded us that these metrics are important but insufficient on their own, as they often don’t address the complexity of interaction between human and natural systems over time.

Reid challenged us to think beyond these metrics of sustainability and focus on regeneration – a continual process of rebirth that requires not only the restoration of natural systems but an ongoing, evolving relationship between natural and human systems. He shared that in his experience, it takes time to understand an ecological system, and offered a few key points to define a regenerative, systems-based approach to design:

relationships are regenerating, not buildings

lists are an incomplete way to know a place

any system is made up of invisible patterns and relationships , both natural and human

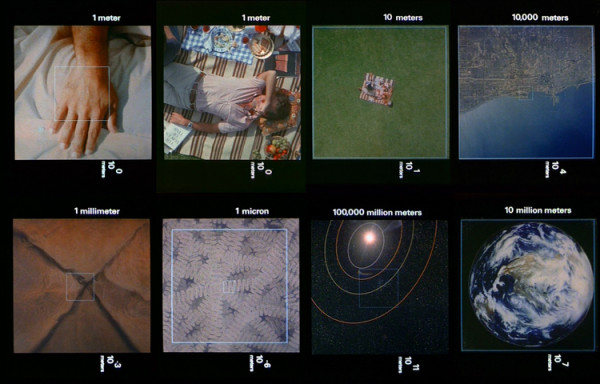

Designing a regenerative future for any ecosystem requires first understanding the system – discovering its patterns and relationships in order to engage with them. As you might imagine, uncovering invisible patterns in an ecosystem is not a strictly linear process (this image depicts it nicely). It requires careful consideration, asking us to slow down.

“Slow down” is not a phrase that often finds its way into the design process. In regards to regenerative design, however, it doesn’t necessarily refer to the time required to complete the project. To slow down in this context means to take a more mindful approach to understanding the purpose and potential of the project at the beginning, when many transformative choices can be made.

In the Slow Food movement, for example, “slow” is used as an intentional contrast to “fast” food, but the movement is more about cultivating awareness of our role in the food system, proclaiming that “a better, cleaner, fairer world begins with what we put on our plate – our daily choices determine the future of the environment, economy and society.” There is even a Slow Home movement that has taken a cue from Slow Food, urging alternative approaches to standardized, mass-produced residential development.

Images from the Charles and Ray Eames 1977 film Powers of Ten – a look at the interconnections of scales large and small.

In his book A Pattern Language, Christopher Alexander reminds us that not only are patterns present at various scales in the landscape, but they are connected through scales. Both Slow Food and Slow Home challenge us to address our role in an existing, problematic pattern (fast food or fast homes), and encourage us to exercise our power to choose an alternative pattern. Small-scale choices are integral to large-scale evolution in an interconnected system.

Alexander also urges that “…when you build a thing you cannot merely build that thing in isolation, but must also repair the world around it, and within it, so that the larger world at that one place becomes more coherent, and more whole….” While buildings themselves are not regenerating, they can be a catalyst for evolution within a larger ecosystem. They can help establish regenerative relationships and behaviors.

Consider your home not just as your individual space, but as a piece of the larger system comprised of your neighborhood, your local economy, and your watershed. Which patterns work in your system, and which need to evolve? What role can you play in repairing the world around you?